“When a Traveller tells a tale, they’re listened to.”

It’s 1946, rural Ireland. Josie Connors, a young Irish Traveller, sets up camp with her nomadic family on the edge of Ryan’s farm. When she crosses one of the deeply entrenched cultural lines between her Irish (ethnic minority) travelling community and the Irish (settled) community, we are catapulted through decades of unthinkable consequences. “Stuck between two worlds” in abject isolation and poverty, Josie keeps moving, presented with the most compelling reason of all to survive.

“It is hard not to be struck by the raw emotion generated by Mary Kelly and Noni Stapleton’s outstanding work – Two for a Girl…. this is theatre stripped down to its basics and it works.” Sunday Business Post. Five Stars *****

Two for a Girl is an homage to the intimacy and simplicity of traditional Irish theater, a style that can be as affecting on the back of a cart or the corner of a pub as it can on a formal stage. As Mary Kelly seamlessly embodies the five main characters, you will be drawn across generations and to every corner of Ireland in this unique look at identity, freedom and loss when two distinct Irish communities collide. This is a play about the transformative power and absolute necessity of being heard and bearing witness.

Two for a Girl is an homage to the intimacy and simplicity of traditional Irish theater, a style that can be as affecting on the back of a cart or the corner of a pub as it can on a formal stage. As Mary Kelly seamlessly embodies the five main characters, you will be drawn across generations and to every corner of Ireland in this unique look at identity, freedom and loss when two distinct Irish communities collide. This is a play about the transformative power and absolute necessity of being heard and bearing witness.

“A very moving piece that leaves you walking out of the theatre in a daze with the smell of a campfire in your nostrils.” Doireann ni Choitir UTV.ie

In commemoration of the 100th anniversary of the 1916 Easter Rising in Dublin, ETB | IPAC continues its exploration of new Irish theater with Mary Kelly’s and Noni Stapleton’s Two for a Girl. The play is performed by Mary Kelly, a Berlin-based actor and playwright who is part of Berlin’s burgeoning international Freie Szene.

MARY KELLY is an actor and playwright. She graduated from the Gaiety School of Acting, Dublin, in 2002. Five of her plays have been produced, two of which are published: Unravelling the Ribbon and Two for a Girl. Unravelling the Ribbon toured Ireland in 2008, and had its U.S. premiere in 2010 with the Tennessee Women’s Theater Project. It has recently been translated into French. Since moving to Berlin, Mary was commissioned and has written The Scarlet Web for Big-Telly Theatre Company, Northern Ireland.

Mary’s theater work includes Christine Linde in A Doll’s House (Alan Stanford, Second Age Th. Co. Ireland), Lydia in All My Sons (Robin Lefevre, The Gate Theatre) and The Little Mermaid world tour (Big-Telly Th. Co.). TV and film work includes Parked with Colm Meaney (Ripple World Pictures), Fran (Setanta and TV3) and The Clinic (RTE). Radio work includes The Hit List with Brendan Gleeson, written and directed by John Boorman, and Mayday written and directed by Veronica Coburn.

Mary’s previous work at English Theatre Berlin includes: two staged readings of new Irish drama during English Theatre Berlin | International Performing Arts Center’s Irish festival The Full Irish (2013) and in ETB | IPAC’s Science&Theatre production of Isaac’s Eye by Lucas Hnath (2013/2014/2015). In January 2016, Mary presented her prose work within the literary event Inkblot Berlin at ETB | IPAC.

Two for a Girl is published by The Stinging Fly Press, Dublin.

Photo: Gerald Wesolowski

Two for a Girl is an homage to the intimacy and simplicity of traditional Irish theater, a style that can be as affecting on the back of a cart or the corner of a pub as it can on a formal stage. As Mary Kelly seamlessly embodies the five main characters, you will be drawn across generations and to every corner of Ireland in this unique look at identity, freedom and loss when two distinct Irish communities collide. This is a play about the transformative power and absolute necessity of being heard and bearing witness.

Two for a Girl is an homage to the intimacy and simplicity of traditional Irish theater, a style that can be as affecting on the back of a cart or the corner of a pub as it can on a formal stage. As Mary Kelly seamlessly embodies the five main characters, you will be drawn across generations and to every corner of Ireland in this unique look at identity, freedom and loss when two distinct Irish communities collide. This is a play about the transformative power and absolute necessity of being heard and bearing witness.

Supported by Hauptstadtkulturfonds

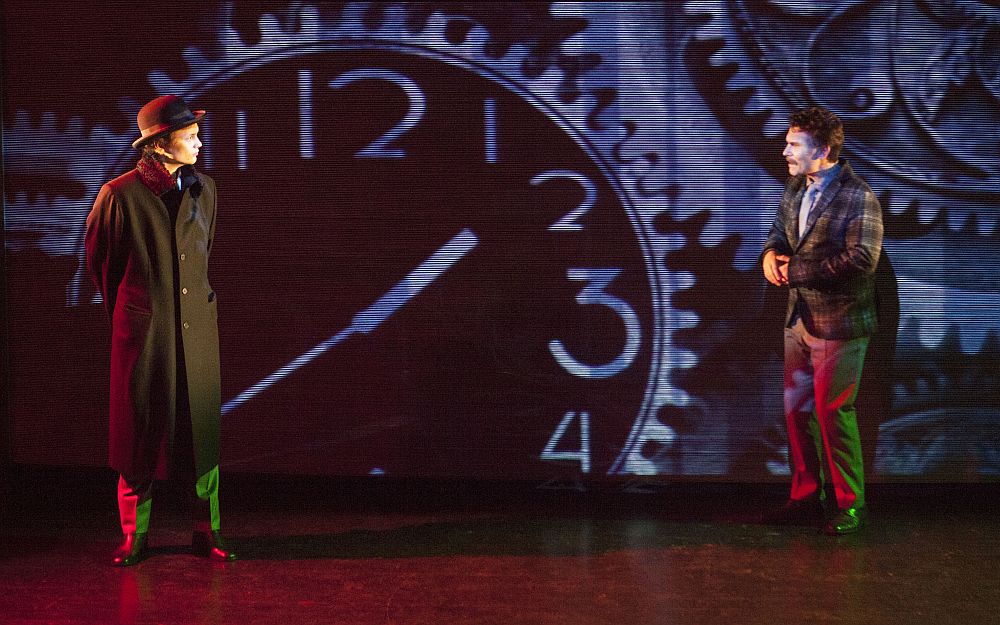

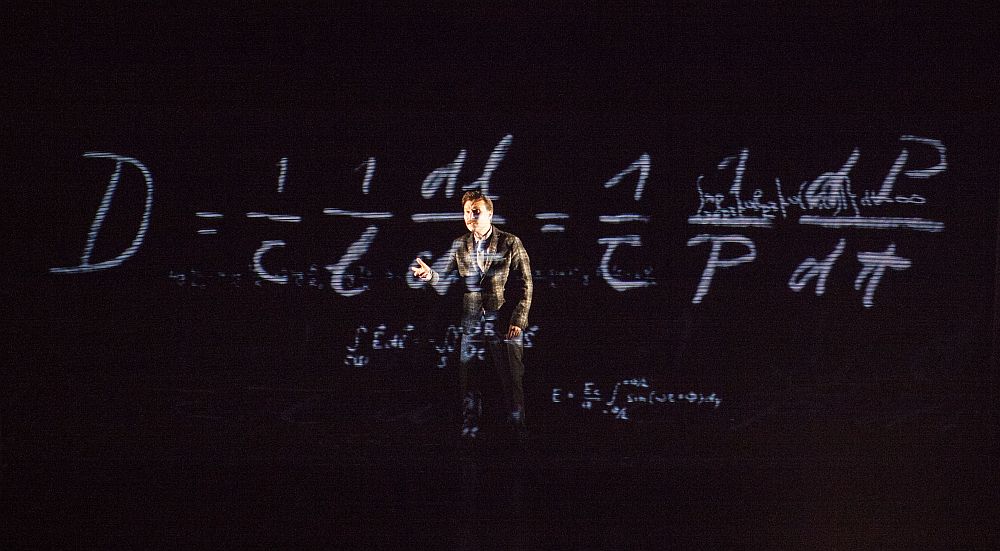

Supported by Hauptstadtkulturfonds The foundations of European society were being shaken and World War I was about to deal them a final blow when Albert Einstein presented his general theory of relativity in Berlin on November 25, 1915 – now even space, time, gravity and the cosmos were no longer what they used to be. Everything seemed to be relative, all conventions were crumbling and God had left the building.

The foundations of European society were being shaken and World War I was about to deal them a final blow when Albert Einstein presented his general theory of relativity in Berlin on November 25, 1915 – now even space, time, gravity and the cosmos were no longer what they used to be. Everything seemed to be relative, all conventions were crumbling and God had left the building. Within a few years, Einstein emerged as an internationally-acclaimed scientist comparable to Copernicus or Newton. In Stockholm, however, the Nobel Committee for Physics resisted the massive support for his theories of relativity. What was at stake was whether or not a prize should go to Einstein and his “corrupt Jewish science,” as it was called by those who would soon instigate the next European catastrophe.

Within a few years, Einstein emerged as an internationally-acclaimed scientist comparable to Copernicus or Newton. In Stockholm, however, the Nobel Committee for Physics resisted the massive support for his theories of relativity. What was at stake was whether or not a prize should go to Einstein and his “corrupt Jewish science,” as it was called by those who would soon instigate the next European catastrophe. Robert Marc Friedman’s new play tells a tale of strained friendships, the search for new perspectives and scientific integrity against a backdrop of a fierce battle between uncompromising opponents in a decaying society.

Robert Marc Friedman’s new play tells a tale of strained friendships, the search for new perspectives and scientific integrity against a backdrop of a fierce battle between uncompromising opponents in a decaying society.

He doesn´t know a thing about art. But being a former bouncer, Dave gets hired to guard a controversial piece of art. “Jesus on the Cross” is ten feet high by six feet wide and was created in a, well, let’s say, different sort of way. There are people out there who won´t like it, and there are many ways of looking at it. While Dave develops his own relation to art and this particular piece, he begins defending it against his wife, the media and a whole bunch of religious fanatics. Then the shit hits the fan. In the end, his troubles come from an unexpected side.

He doesn´t know a thing about art. But being a former bouncer, Dave gets hired to guard a controversial piece of art. “Jesus on the Cross” is ten feet high by six feet wide and was created in a, well, let’s say, different sort of way. There are people out there who won´t like it, and there are many ways of looking at it. While Dave develops his own relation to art and this particular piece, he begins defending it against his wife, the media and a whole bunch of religious fanatics. Then the shit hits the fan. In the end, his troubles come from an unexpected side. Nick Hornby is an English writer born in 1957 in Surrey. He studied English at Jesus College, Cambridge. His first book, Fever Pitch (1992), was a huge success, followed by High Fidelity (1995) which was made into a film starring John Cusack and a Broadway musical. About a Boy, also adapted into a film starring Hugh Grant, came out in 1998. Hornby´s other novels are How to be Good (2001), A Long Way Down (2005), Slam (2007), Juliet, Naked (2009) and Funny Girl (2014). His short story collection includes Faith (1998), Not a Star (2000) and Otherwise Pandemonium (2005). The film adaptation of Colm Tóibín´s novel Brooklyn for which Hornby wrote the screenplay was released in 2015. He has written numerous essays mostly on music and literature. Nick Hornby received, amongst numerous other awards and prizes, an Oscar nomination for his screenplay for Lone Scherfig´s film An Education (2009). He has been given the name “The maestro of the male confessional” for the brilliant portrayal of his male characters in his novels.

Nick Hornby is an English writer born in 1957 in Surrey. He studied English at Jesus College, Cambridge. His first book, Fever Pitch (1992), was a huge success, followed by High Fidelity (1995) which was made into a film starring John Cusack and a Broadway musical. About a Boy, also adapted into a film starring Hugh Grant, came out in 1998. Hornby´s other novels are How to be Good (2001), A Long Way Down (2005), Slam (2007), Juliet, Naked (2009) and Funny Girl (2014). His short story collection includes Faith (1998), Not a Star (2000) and Otherwise Pandemonium (2005). The film adaptation of Colm Tóibín´s novel Brooklyn for which Hornby wrote the screenplay was released in 2015. He has written numerous essays mostly on music and literature. Nick Hornby received, amongst numerous other awards and prizes, an Oscar nomination for his screenplay for Lone Scherfig´s film An Education (2009). He has been given the name “The maestro of the male confessional” for the brilliant portrayal of his male characters in his novels. Within a few years, Einstein emerged as an internationally-acclaimed scientist comparable to Copernicus or Newton. In Stockholm, however, the Nobel Committee for Physics resisted the massive support for his theories of relativity. What was at stake was whether or not a prize should go to Einstein and his “corrupt Jewish science,” as it was called by those who would soon instigate the next European catastrophe.

Within a few years, Einstein emerged as an internationally-acclaimed scientist comparable to Copernicus or Newton. In Stockholm, however, the Nobel Committee for Physics resisted the massive support for his theories of relativity. What was at stake was whether or not a prize should go to Einstein and his “corrupt Jewish science,” as it was called by those who would soon instigate the next European catastrophe.